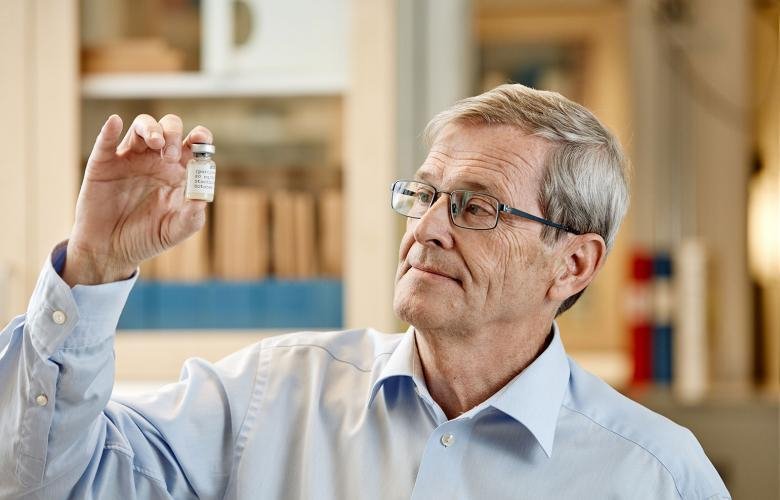

Tore Curstedt's Curosurf helped millions of preterm babies

In the spring of 2016, KI researcher Tore Curstedt was nominated for a Lifetime Achievement Award by the European Patent Office for having devoted his life to Curosurf, a drug that has helped to activate the lungs of millions of preterm babies.

Tore Curstedt is now retired but turns up almost daily to his office at Karolinska University Hospital. The room is plainly furnished, with shelves of files, light-wood table tops and chairs upholstered in blue.

“You can’t just stop working when you realise that all the research you’ve sweated over has maybe saved the lives of half a million babies,” he says.

Every morning, he gets off the bus a few stops from the university and walks the rest of the way through the northern cemetery, passing by the gravestones of Alfred Nobel, Ingrid Bergman, Ernst Rolf and Folke Bernadotte, to name just a few of the great Swedes resting there.

“I walk through the different plots memorising the names on the stones and the places where famous people lie. It’s a bit of morning exercise for both brain and body,” he chuckles.

Tore Curstedt was born in 1946, the only child in the Piteå household. His father was a mental health nurse and his mother a housewife. He obtained such good school grades that he could start considering medical studies, so he applied to Karolinska Institutet, enticed not only by the programme but also by the thought of scientifically studying the workings of the body to understand his own intestinal health problems better. And thus he embarked on his medical career.

He was in his teens when the papers were writing about President Kennedy’s son, who, in spite of the USA’s medical expertise, died in a Boston hospital just a few days old from lung failure. Back then, ninety percent of preterm babies died. It is not unlikely that it was then the seed of a challenging thought was planted in Tore Curstedt’s mind.

Activate the lungs of preterm babies

Teaming up with fellow-researcher Bengt Robertson, he conducted experiments at Karolinska University Hospital to produce a drug able to activate the lungs of preterm babies. The drug was called Curosurf – Cu as in Curstedt, Ro as in Robertson, and Surf as in Surfactant, the substance that in healthy, fully developed humans regulates surface tension in the lungs and prevents them from collapsing on exhalation. A substance that very premature babies have not had time to develop.

His partner Bengt Robertson died in 2008, but Tore Curstedt has continued to research.

He never forgets an occasion over forty years ago when the two of them received a phone call from a doctor at the neonate ward at St Göran’s Hospital. It was an emergency: a preterm baby girl was dying because her lungs, despite their desperate attempts to save her, were failing to start.

With only hours to go, the doctors and the girl’s parents agreed that it was worth one last shot, even though the drug had not been fully developed or even tested on humans. They had successful animal trials behind them, but had yet to reach the stage of human trials and ethical review permits.

The attempt was signed and approved by all concerned and what happened a few hours later seemed to them nothing short of a miracle. The drug was injected into the girl’s trachea and in no more than five minutes her blue pallor changed to pink before settling into a normal oxygenated hue.

“An hour later her lungs were working normally and we could take her off the oxygen,” says Tore Curstedt. “It was one of the most magical moments of my life. That was it - there was only one way to go: forward!”

Swedish industry turned them down

But it was hard getting the industry to listen. Pharmacia turned the drug down – too high marketing costs and too small a market, they said. And finding Karolinska Hospital also rather diffident, Curstedt and Robertson turned to Europe. In Italy they found a private drug company, Chiesi Farmaceutici, that was willing to take on the product and patent it. Curstedt and Robertson received royalties.

“If we’d been a bit more money-minded we’d have become multimillionaires almost overnight,” says Dr Curstedt, “But that doesn’t bother me. When I meet young people and the parents of children who all want to thank me, even hug me, that’s payment enough for me.”

Over the years, scientists have tried to synthesise surfactants. But so far, no one has come close to Curosurf’s successful solution that uses biological material extracted from pig lungs. While the drug was being developed, pig lungs could be obtained for free from Swedish abattoirs; despite this, the process is a costly one, as the pig lung yields just a fraction of a gram, enough for two, maybe three babies.

“We’re therefore trying to develop a synthetic solution so we don’t have to rely on pigs,” says Tore. “It’ll take some years, and I hope I’m there all the way to the point when this particular scientific nut is cracked.”

People come up to thank him

Curstedt and Robertson’s invention is estimated to have helped three million babies and saved the lives of at least half a million preterm babies around the world. The oldest are today in their thirties, and the medicine is sold in around 80 countries.

Tore Curstedt emanates deep emotion and pride when he talks about these people, who are all alive today thanks to Curosurf.

“I meet them now and again. They come up to me and thank me. One girl who was saved even competed in a memory contest on TV. So sure you can have a perfectly normal life thanks to Curosurf, even if you were born at 28 weeks.”

Text: Matts Heijbel

Translation: Neil Betteridge

Photo: EPO

Short facts about Tore Curstedt

Age: 70.

Work: Docent at the Department of Molecular Medicine and Surgery in the “Clinical chemistry and coagulation” research group at Karolinska Institutet and Karolinska University Hospital.

Family: Wife Sol-Britt Curstedt, also a doctor. Two adult children and five grandchildren.

Lives in: Edsviken, Sollentuna.

Interests: Golf, shares and travel. He has been to over 100 places around the world, including Svalbard, North Korea, Antarctica, Burma and Transnistria.