Celebrity worm researchers hold Nobel lectures

Moon landings, worms and micro-RNA are just three shared interests held by Victor Ambros and Gary Ruvkun, who told the story of how they first aimed for the stars and achieved a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in their Nobel lectures with humor and erudition.

Outside Aula Medica, the queue for this year’s Nobel lectures stretched into the distance in the December chill, and going by one of the topics of conversation snapped up, the line has grown longer by the year.

Against the backdrop of an expectant buzz, the lecture hall gradually filled as members of the public, students and professors – many dressed up in their fineries for the lectures and the ensuing invitation-only reception – trooped in to take their seats.

KI President Annika Östman Wernerson opened the event, pointing out in her welcoming address how this year’s Nobel Prize underscored the importance of curiosity-driven research.

“The discovery of fundamental new mechanisms of gene regulation would probably not have been achieved if goals for the research had been predetermined,” she said.

Professor Anna Wedell from the Nobel Assembly then introduced the Nobel laureates, describing how their discoveries have changed our understanding of how genes are regulated.

“We now know that micro-RNAs play important roles in most physiological processes and are involved in a range of human diseases,” she said.

It started with a family outing

The first laurate to address the audience was Victor Ambros, who began by talking about his childhood.

“I think I started out as a scientist,” he said, explaining that his personality has always been a curious and inquisitive one.

One defining moment for him came in 1970, when he had his amateur astronomical observation of a solar eclipse mentioned in a magazine.

“That was the first time I felt like a real scientist,” he said.

The article gave the correct location of his “research station” but omitted to add that it consisted of a family outing with a telescope.

After having studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, he converted from astronomy to biology, inspired by other students who were passionate about the subject.

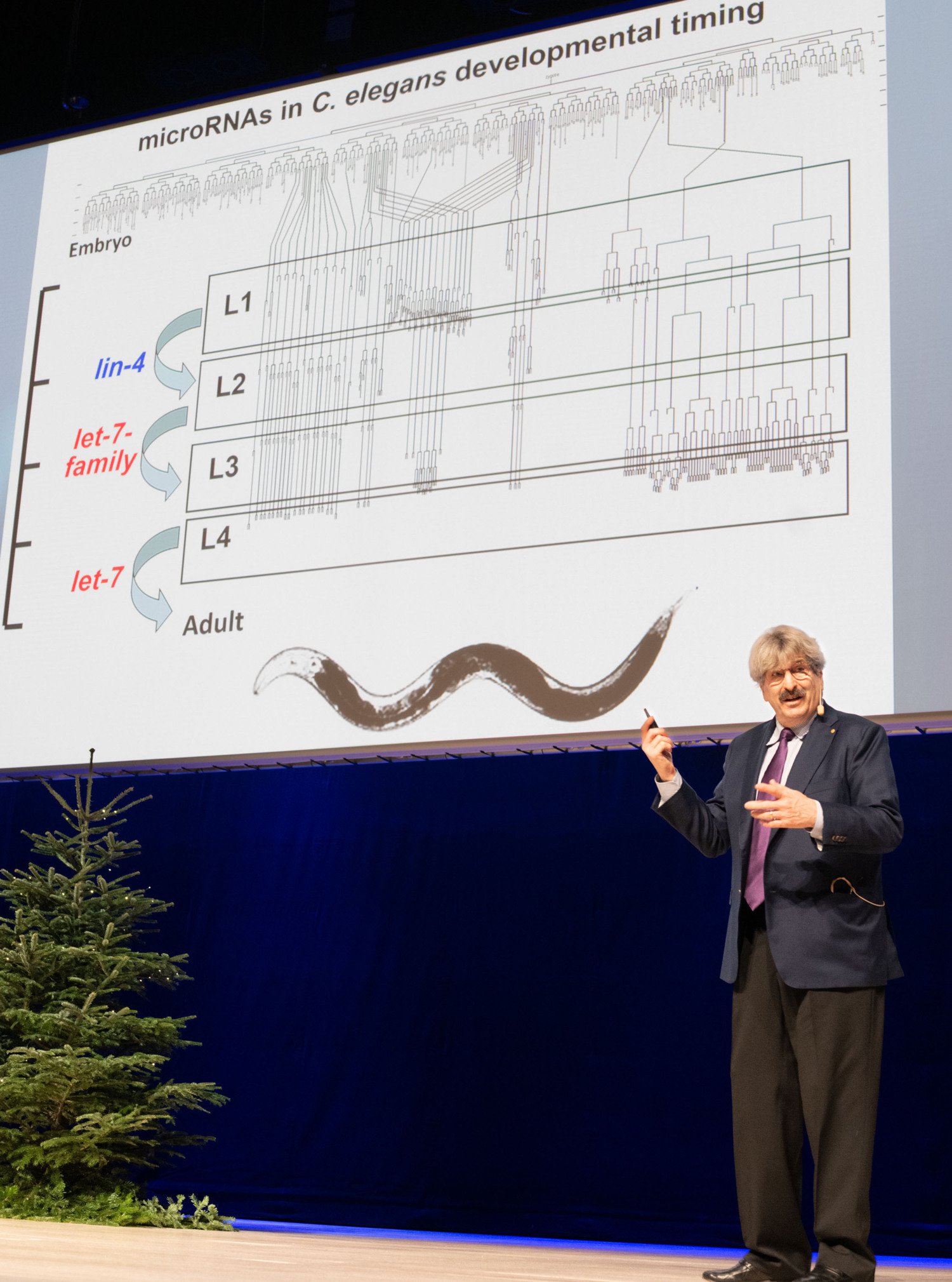

In the early 1980s, a complete cell lineage had been drawn for the tiny roundworm c. elegans. The cell types of the easily cultivated worm always develop in the same order, making it a useful model organism for developmental biologists.

“The big question was how its development was encoded in the genome,” said Dr Ambros.

Two genetic mutations that could disrupt the growth of the worm in various ways piqued the researchers’ interest. Victor Ambros studied the one – lin-4 – while Gary Ruvkun studied the other – lin-14.

Worm Breeder’s Gazette

Gradually, the picture came into focus with the aid of a genome map of the worm produced by like-minded scientists, and with the internet in its infancy, their unpublished results were usually posted in The Worm Breeder’s Gazette.

Then, in 1992, the future Nobel laureates compared their results in a pivotal phone call:

“In that moment, we knew the mechanism,” said Dr Ambros.

It turned out that lin-4 coded for a micro-RNA molecule that matched with a messenger RNA produced by the lin-14 gene, allowing the micro-RNA to prevent it from producing proteins, which was a previously unknown form of gene regulation.

Thousands of different micro-RNAs

Dr Ambros then described how knowledge has advanced since then. Today, scientists know that there are thousands of different micro-RNAs in humans and other organisms, that they can regulate genes through different mechanisms and that they are involved in a range of diseases.

For example, some types of human developmental disorders are caused by mutations that Dr Ambros has studied in c. elegans, although the step between worm and human is a large one.

“What can these studies in c. elegans tell us about the human condition?” he asked. “Not much in terms of particulars of the gene expression disruptions ... it’s more the character of them.”

Then it was time for Gary Ruvkun to be welcomed up on stage. He thanked the audience for the warm reception and the “lovely” phone call from Stockholm informing him about the Nobel Prize. He then showed a diagram of the developmental history of mutant worm cells and began to talk about his research.

Thriving at the edge of biology

At first, other development biologists found it hard to grasp the approach of the worm community, he explained.

“Worms were sort of an outlier in biology, but we kind of liked it!” he said.

Another slide showed how a mutation for a micro-RNA causes changes in the “racing stripes” that run along the length of the worm’s body. The same micro-RNA was later found in other animals, including zebra fish, and in the human brain.

“This told us that micro-RNAs were going to be in many different organisms,” he said.

He went on to explain that micro-RNA is found in both animals and plants, and gave more examples of micro-RNAs that he has studied. One is involved in muscle function, while others are found in specific neurons in the cerebral cortex. Some micro-RNA is active in plants, but there it operates in a different way.

800 person-years in the lab

Some organisms, such as scorpions and spiders, are especially good at amplifying small RNA molecules, which can provide protection against viruses – a sign, according to Dr Ruvkun, that the organism in question is “badass”.

“Worms are tougher than we thought and we should respect that toughness,” he said.

He closed by thanking all the current and former members of his lab, having calculated that all in all they have worked in the lab for 800 person-years, 40 of which he himself accounted for.

“When people leave my lab, there’s a hole ... Yes, I’m an important part of it, but not at all the most important part,” he said, reserving a special mention for his administrator, who has been the soul of the lab for 26 years.

He ended where Dr Ambros began – by talking a little about himself, as pictures of a six-year-old’s somewhat flawed model of the solar system and a teenager’s home-electronics project flashed past.

When he was a little older, he spent a year on the road in South America and another living in his van.

US space programme inspired a generation

Then his interest in science took over, the US space programme proving a major source of inspiration.

“It inspired a whole bunch of nerds in my generation to become scientists,” he said.

He talked about his Jewish background and how when he was little, he felt he bonded with TV comics. Humour, said Dr Ruvkun, is to look at the world from a different angle, which is very scientific. The question “How funny are you?” should therefore be a criterion for selecting postdocs, he joked in closing.

Once the applause had died down and the hall began to empty, up front things had become all the livelier, as fans crowded onto the stage to get autographs and take selfies with the day’s celebrity duo.

Text: Ola Danielsson

Translation: Neil Betteridge