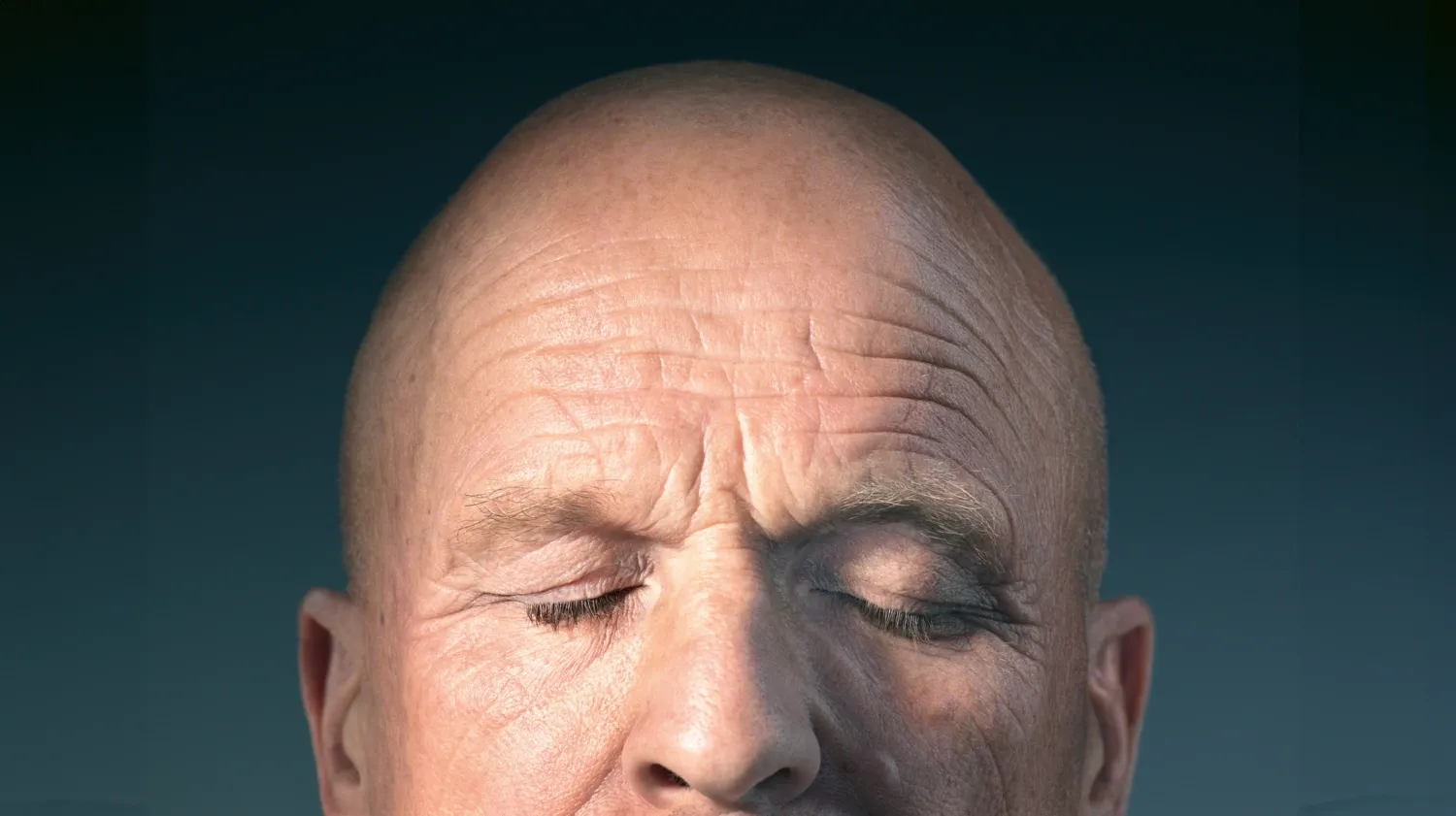

What your brain is up to when resting

When we are not doing anything in particular, the brain is still busy producing thoughts and daydreams. Research shows that mental chatter increase if we are sleep deprived and can sometimes even become a barrier to sleeping. But there are techniques for those who need a break from their thoughts.

Text: Ola Danielsson, first published in Medicinsk Vetenskap nr 1 2025

After a run or a long walk, it is nice to relax and let the muscles rest. The brain also needs a break from impressions and mental work - but try to think about nothing for a while, and you may find that even more thoughts arise.

”From a psychological perspective, rest is difficult to define,” Peter Fransson, Professor of Brain Systems Physiology explains. He has researched the brain's resting state - that is, what the brain does when it is not doing anything in particular.

Previously, researchers thought that brain activity should decrease when it goes from focused thinking on a task to just resting. But that view changed as early as the 1930s when EEG, a technique for measuring brain waves with sensors placed on the head, was invented. Researchers then discovered that the brain is always more or less active, but that brain waves differ depending on whether, for example, we are awake or asleep (see box).

The awake brain is constantly occupied with basic bodily functions, but also with generating thoughts. “Thinking about nothing is a difficult task,” says Peter Fransson.

”It is very difficult to do. After a while, most people’s thoughts start to wander. For example, you start thinking about what you did yesterday, or that it is grandma's birthday tomorrow. Should I do this or that? It's an inner monologue that is constantly ongoing, you start talking to yourself,” he says.

This type of thoughts is mainly generated by a specific network of areas in the brain that are activated when we are not doing anything in particular. It is called the default mode network and gives rise to daydreams and thoughts about the past and future. It also works when we solve tasks that involve ourselves and our relationship to others, such as when we consider moral questions.

“The default mode network is in various ways related to the sense ofself . It works when we look inside ourselves,” says Peter Fransson.

There are also many other networks in the brain that serve different functions. A kind of counterpart to the default mode network is the executive network, which is active when we focus on an outward-directed task.

Peter Fransson has discovered that these two networks are often anti-correlated - when activity is high in one, it is lower in the other - and that there is a spontaneous switching between them even when we are doing nothing.

“There is a fundamental duality, a kind of yin and yang in the brain. When you are lying around doing nothing, you constantly oscillate between these states,’ says Peter Fransson.

The default mode network is also present in other animals such as mice and monkeys. It is reasonable from an evolutionary perspective that the brain works this way according to Peter Fransson.

”These are my speculations, but the balance between these networks may have developed so that we can have an inner life while being alert to our surroundings. When we lived on the savannah, you could not walk around daydreaming all the time. You had to be alert to threats or other dangers,’ he says.

Not fully connected in infants

In infants, the default mode network is not fully connected. It is only at the age of two that it begins to have the appearance and connections that we have as adults,’ Peter Fransson has shown. This likely has significance for children's sense of self - how it feels to be a baby.

“Possibly, it can also explain why we do not have memories from an early age,” he says.

‘There are large individual differences in what our brains do when we are just being. The activity in the default mode network is a kind of cognitive fingerprint that researchers are now trying to decipher.

”The default mode network is involved in reflecting how we are as people, what mental foundation we have,” says Peter Fransson.

The default mode network likely also has its special signature in many other diagnoses, such as ADHD, autism, fibromyalgia and Alzheimer's disease, something that Peter Fransson is studying together with other researchers.

Just being can be restful and pleasant - but not always. Some people, for example, easily fall into negative thoughts about themselves, ruminating on problems. Even then, the default mode network is active.

”There are studies suggesting that the default mode network is overactive in deep depression,” says Peter Fransson.

‘One way to temporarily turn down the volume of the default mode network is engaged in something that requires concentration, such as solving a crossword puzzle.

Another option might be to learn to meditate. Those who meditate quickly discover how thoughts tend to wander in different directions. Through various meditation techniques - such as focusing on breathing and letting thoughts pass without attaching to them - one can practice being more in the present moment.

There are also studies linking meditation to reduced and altered activity in the default mode network among seasoned meditation practitioners. Peter Fransson has not researched this but is not opposed to the idea that there might be something to it.

”I do not think we can control the fundamental pattern - the switching between internal and external attention during rest is beyond our control. But there may certainly be ways to quiet the activity a bit,’ he says.

Sleep affects daydreaming

Another factor that affects the tendency to drift into spontaneous thoughts and daydreams is how much we have slept. This is explained by Per Davidson, a researcher at the Department of Clinical Neuroscience at Karolinska Institutet, who studies the importance of sleep for emotionally charged memories.

In his studies, participants experience something, such as seeing disturbing images. Then they either sleep or stare at a wall - and afterwards, their memory or the experience and the strength of the emotional response are tested.

For practical reasons and consideration for the study participants, the research is done on naps. It would be too boring for the control group otherwise. They are not allowed to engage in distractions such as checking their mobile phones or watching TV, but must just let time pass.

The background to the research is that sleep is considered to strengthen memories - if we have learnt something, it sticks better if we sleep afterwards compared to if we stay awake. But according to Per Davidson, it is unclear exactly what role sleep plays.

”We do not know to what extent sleep has an active memory-strengthening role. ‘Sleep is also a passive state where we are shielded from new impressions,” he says.

Understanding how sleep affects emotional memories can be important in certain clinical situations, such as caring for people who have experienced car accidents or other traumatic events.

”If sleep and wakefulness are found to have different effects on how we process an emotional experience, it should influence how we approach whether to sleep or not after such an event,” explains Per Davidson.

According to Per Davidson, research shows that sleep generally strengthens memories. But in his experiments, he has not been able to see that sleep reduces the emotional charge in memories compared to wakefulness.

He has also reviewed other research in the field and found that the results are mixed. He aims to address this with a new project called many naps, where many laboratories will conduct the same experiments to increase the reliability of the results.

It is a common belief that things feel easier after a good night's sleep. According to Per Davidson, it is true that sleep generally improves our mood, but it may not make the memory of specific negative experiences feel better.

”Go to bed, and maybe you will feel better tomorrow is all one can say,’ he says.

But when it comes to a specific outcome measure, the results are more consistent, although Per Davidson emphasises that this also needs to be confirmed in larger studies.

”It seems that sleep makes negative memories less intrusive. People who have experienced something negative are more likely to involuntarily think about the memory if they were awake after the event, compared to if they had slept,” says Per Davidson.

The explanation, he believes, may be that sleep consolidates the memory in a way that makes it less messy and fragmented, which might make it easier to voluntarily control when to think about it and when to not.

It is also known that sleep deprivation leads to increased daydreaming and difficulties in voluntarily controlling which memories and thoughts come to mind in general. Daydreams can be positive, playful or constructive thoughts that enhance one’s well-being. But they can also be disturbing thoughts that make it difficult to focus or are that are associated with negative emotions.

A type of negative daydream that worsens with sleep deprivation can be involuntary memories. ‘The memory of a negative event itself may change with sleep, but sleep deprivation makes us less able to control our concentration,’ explains Per Davidson.

‘So, sleeping properly can be helpful for those troubled by negative daydreams. And during sleep, we also get a break from our constantly spinning thoughts. But the brain continues to be active.

The brain takes no nap

“When we sleep, we do not take in as many impressions from the outside world. But it is not that the brain does nothing. It does something else,’ says Susanna Jernelöv, researcher at the Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet.

Deep sleep, the sleep stage considered most important for recovery, accounts for about 20 percent of sleep time. During this stage, brain activity slows down, and we are difficult to wake.

During REM sleep, when we dream the most, the brain is about as active as when we are awake, but the activity varies between different parts. The front part of the brain, which is important for logical thinking, rests, while, for example, the amygdala, which is involved in processing emotions, is more active.

Like daydreams, night dreams can be both pleasant and less pleasant experiences. For some, recurring nightmares become a problem, and then sleep is not very restful. But it can actually be treated, explains Susanna Jernelöv.

A method that she has worked with and which she says has research support is called image rehearsal therapy. It involves writing down the dream as a story and then changing the ending - for example, if you go down a staircase in the dream and meet a witch, in the new story, you can go out of the house instead.

”Then you practice imagining the new story as inner images. The treatment is based on the idea that dreams are images rather than words. It has been shown that this can lead to recurring nightmares changing,” says Susanna Jernelöv.

In the borderland between sleep and wakefulness, strange experiences can also occur. Some people experience hypnagogic hallucinations - intense dream images while being conscious and awake.

“One possible explanation is that you switch back and forth between different sleep stages. But a newer hypothesis, which can explain these phenomena very well, is that one part of the brain is dreaming while another part is awake,” says Susanna Jernelöv.

Recently, researchers have become increasingly interested in what happens in different parts of the brain during sleep.

”People have started talking about local sleep, that the brain maybe rest one or more parts at a time. There are also studies suggesting that the parts that have been most active during the day are the ones that then does the most deep sleeping,” says Susanna Jernelöv.

This is a useful perspective when treating sleep problems, she explains.

”People often think that they need to rest to become alert, and people with sleep problems often stay in bed longer to try to get more sleep. But it rarely works,” says Susanna Jernelöv.

According to her, it is better for sleep to be active when awake, compared to lying in bed in a semi awake state. Reducing the time spent in bed is called sleep restriction, and in Susanna Jernelöv's studies it has been shown to work well against insomnia - difficulty falling asleep or maintaining sleep during the night.

”Initially, you often sleep less than before, but after a few weeks, you usually start sleeping better instead,” says Susanna Jernelöv.

For those lying awake, it is also common for thoughts to feel more unruly than during the day. The problem-solving ability is impaired and it is difficult to make oneself sleepy by thinking. According to Susanna Jernelöv, it is best in this situation to change strategy so that the brain finally gets its much-needed rest.

”Write down your thoughts to get them out of your head. Then get up and do something else for a while and try again later,” she says.

Your brain is always oscillating

Different types of brain waves, synchronised electrical activity in the brain's nerve cells (neurons), can be measured depending on what is happening in the brain at the time.

Gamma waves (30-80 Hz): Problem-solving with coordination of cortical areas.

Beta waves (14-30 Hz): Active or anxious thinking, concentration and excitement.

Alpha waves (8-13 Hz): Typical for people who are awake but have their eyes closed and are relaxing or meditating.

Theta waves (4-7 Hz): Can be measured during deep relaxation or meditation, but also during REM sleep.

Delta waves (1-3 Hz): Observed in individuals who are in deep sleep or coma.

Sources: Brainfacts.org, Theconversation.com/Alpha, beta, theta: what are brain states and brain waves? And can we control them?, Per Davidson