Long live the liver!

Many Swedes live with fatty liver – and it doesn’t have to be dangerous. But for some, it kicks off a course of disease in which persistent inflammation leads to cirrhosis. Medicinsk Vetenskap has talked to researchers who look after the liver – the behemoth of the belly that has a somewhat magical ability to recover, along with enormous overcapacity.

Text: Annika Lund; first published in the magazine Medicinsk Vetenskap nr 4 2023 / Spotlight on the liver

The liver is located high up in the abdomen, next to the stomach and protected behind the ribcage. Most of it is located in the right half of the body, but its protuberant “snout” reaches over to the left part of the abdomen. It is a large organ, with a normal weight between 1.2 and 1.5 kilogrammes.

This brown behemoth brims with mystery. For example, it has an incomprehensible amount of excess capacity. It is possible to remove four-fifths of the liver – perhaps more – without the organ losing function. It can also regenerate its lost part. Thus, a living person can donate a piece of their liver for transplantation. Both parts will grow – the liver left behind in the donor and the portion surgically inserted into the recipient. However, this technique is usually only used if it is a child who needs a new liver. In 2022, none of the liver transplants performed in Sweden involved a living donor.

But this overcapacity has a nasty downside. A liver can become very seriously ill, without anyone noticing. A silent and insidious breakdown can occur, without signs of liver disease and without stomach pain – we have no sensation in the liver. By the time symptoms appear, the damage can be far advanced, in the worst case incurable and fatal.

“One challenge for us liver doctors is to succeed in identifying more people with liver disease at an earlier stage, when the disease can be slowed down and ideally reversed. But it’ll take a lot to achieve that goal. We need to get better at communicating knowledge about the liver to the public, while at the same time the healthcare system needs to do more to examine patients at high risk of serious liver disease,” says Hannes Hagström, an associate professor at Karolinska Institutet’s Department of Medicine, Huddinge.

Disease usually develops slowly

A liver can be acutely damaged by an accident or severe poisoning, for example from medications. However, the vast majority of cases of liver damage are due to disease that develops slowly over many years. In principle, all liver disease follows the same course, which starts with something irritating or disturbing the liver. Different things can do this, but two examples are alcohol and the hepatitis C virus. In response to this stimulus, inflammation may occur. When it heals, fibrosis – scar tissue – is formed. If what is interfering with the liver remains in the body, more fibrosis will form in a process in which a healthy liver is replaced by stiff scar tissue. Finally, the compounded damage reaches the end stage of liver disease – cirrhosis of the liver. In this phase, the liver tries to form more cells than normal, which increases the risk of mutations. This can lead to liver cancer. The cirrhosis itself can also become so widespread that the liver can no longer function. The symptoms appear late in the course of the disease, when a cancer or advanced cirrhosis has already developed.

The most common starting point for liver disease is fatty liver. Several roads lead to that point. One of them is alcohol consumption, in which long-term use causes the liver to accumulate fat. But being overweight or obese can also lead to fatty liver. And when you examine it under a microscope, a liver with stored fat looks exactly the same, regardless of whether it has been caused by alcohol or other lifestyle habits. For this reason, it was not until the 1980s that doctors understood that fatty liver could have a background other than alcohol consumption, says Hannes Hagström.

“Before that, doctors assumed that all patients with fatty liver had been drinking too much alcohol. When patients with fatty liver swore they weren’t heavy drinkers, no one believed them,” he says.

Photo: Daniel Nilsson

Photo: Daniel NilssonMartin Bengtsson changed his lifestyle for the sake of his liver

When Martin Bengtsson found out he had fatty liver disease, he decided to start eating healthier and exercising more. "A lot of people think you can't do anything about fatty liver - but you can," he says.

Hannes Hagström has conducted a review of trends in liver disease in Sweden between 2005 and 2019. Some diseases have become less common. For example, new, curative medications for hepatitis C were launched during the period studied. As a result, fewer and fewer Swedes are getting cirrhosis of the liver due to this viral disease, which in Sweden is spread mainly when people inject illegal drugs and share syringes.

Other diseases have become more prevalent. This includes autoimmune hepatitis, a disease whose cause has yet to be identified. The researchers also have no explanation for the increase in cases, but note that it has been noticed in several other countries, as well.

Fatty liver disease on the rise

But the most striking trend is that liver disease with lifestyle-related causes is increasing sharply – very sharply. Cirrhosis as a result of alcohol abuse increased by 47 per cent during the period, and cirrhosis of the liver as a result of being overweight or obese jumped by 87 per cent. This type of cirrhosis, caused by alcohol or diet, is the most common cause of death from liver disease. The number of liver cancer cases also rose during the period.

The figures are reflected in transplant statistics. In 2022, alcohol-induced cirrhosis of the liver was the most common reason in the Nordic countries for someone needing a new liver, according to statistics from the coordination organisation Scanditransplant. Other common causes were primary liver cancer and the disease PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis.

But the researchers believe there will be a shift here. In the United States, for example, a very common reason for liver transplantation is that someone has cirrhosis of the liver as a result of being overweight or obese. And researchers say it is likely that this route to liver replacement will become more common in Sweden, too.

It takes many years to develop cirrhosis of a fatty liver. And according to the study by Hannes Hagström, fatty liver caused by being overweight or obese– but that has not yet become cirrhosis of the liver – increased by 217 percent between 2005 and 2019.

However, these figures entail many uncertainties. They are based on what doctors have reported to the register of the National Board of Health and Welfare. No one actually knows how many Swedes have fatty liver as a result of being overweight or obese – making it impossible to know exactly how much more common the disease has become.

But it is very common. On a global scale, it is estimated that one in four adults has a fatty liver as a result of being overweight or obese.

Hannes Hagström recounts a study conducted in Dallas, Texas in the United States in which 2,300 people from the normal population were examined with an MRI camera, making it possible to visually assess how much of their liver consisted of fat. More than five per cent is considered fatty liver. And in Dallas, one in three people in the normal healthy population was found to have fatty liver, without knowing it.

“But obesity is more common in Dallas than it is in Sweden, for example. If you translate the figures to Swedish obesity statistics, it’s reasonable to believe that about a million adult Swedes have fatty liver. But that’s just a rough estimate,” says Hannes Hagström.

Not dangerous in itself - but a risk factor

Fatty liver is not dangerous to live with in itself, he explains. An otherwise normal fatty liver that has no signs of inflammation can be likened to slightly elevated blood pressure – it is a risk factor for disease, not a disease in itself.

"A slight increase in blood pressure doesn’t cause any symptoms that the patient notices. But for a minority of them, that higher blood pressure may eventually cause a stroke. It’s pretty much the same with fatty liver – it’s not a disease in itself, but for a smaller group, it marks the start of a course that can lead to serious liver disease,” says Hannes Hagström.

It is when inflammation comes into play that fatty liver can become dangerous to one’s health. When inflammatory foci heal, they are transformed into scar tissue, fibrosis. This takes place in a continuous process that lasts as long as what is irritating the liver remains in the body. If the alcohol, fat or virus causing the damage is eliminated, the process stops – and the magically regenerating liver can recover.

“But if cirrhosis has already developed, it’s impossible to ever get back to a completely healthy liver. But even liver cirrhosis can show certain signs of some healing,” says Hannes Hagström.

However, not everyone with fatty liver develops inflammation. According to the researchers, genetic factors play a role here, but the question of why some people can live healthy lives with a fatty liver, while others move towards cirrhosis of the liver, is a major research question.

According to Hannes Hagström, it is estimated that no more than five per cent of the million Swedes who have fatty liver will eventually develop cirrhosis. The numbers are vague, not least because it is unclear how many people actually have fatty liver.

The challenge of preventing cirrhosis

But the key questions are clear: How can we determine whose fatty liver will develop into cirrhosis? And how do we identify these people before that happens?

“Well, we’re facing a major challenge there. You could say we’re trying to find the proverbial needle in a haystack. But we still have certain procedures in place,” says Hannes Hagström.

It takes several decades to go from fatty liver to full-blown cirrhosis, in which the risk of liver cancer is greatly increased. And people can even live with cirrhosis of the liver for many years, without symptoms – cirrhosis is also a multi-stage disease.

The body is initially able to compensate for the deficiencies in the liver. For example, it can create new pathways for the abundant blood flow that passes through the liver – every minute, about a fifth of the body’s blood volume must be channelled through this centrally located giant. However, in cirrhosis of the liver, these passages may be constricted. This can be seen in other parts of the vascular tree, which are affected by overpressure. Small blood vessels in the oesophagus and stomach may expand, develop aneurysms or hernias, and become brittle. All this can be done in secret, in a cirrhosis of the liver that still allows some organ function.

But suddenly, such a vessel can rupture in a so-called variceal haemorrhage. This is a life-threatening event in which the patient starts to vomit large amounts of blood and requires urgent care. Other serious complications include ascites, in which fluid leaks into the abdomen, sometimes in large volumes – perhaps ten litres or even more. Patients may also suffer from acute confusion. In layman’s terms, this can be explained by the fact that the liver no longer fulfils its detoxifying function, resulting in neurotoxicity that affects the brain. Patients can also develop severe infections. These are all signs that the body is no longer able to compensate for the deficiencies of the liver.

“Having decompensated cirrhosis of the liver is a turning point in the disease. From then on, a liver transplant is the only way to ensure survival,” says Hannes Hagström.

Photo: Martin Stenmark

Photo: Martin StenmarkPeter Jonson needed a liver transplant

Peter Jonson needed a liver transplant after unexpectedly learning that his liver was in poor condition. Today he is doing well and does not miss the lifestyle that made him sick. "Non-alcoholic beer tastes really good", he says.

In a study conducted in 2016 in Skåne, more than half of the patients with cirrhosis of the liver were diagnosed in the emergency ward, where they had come to seek treatment for ascites or a variceal haemorrhage, for example. Before that, they seem to have been unaware of the serious state of their own liver.

According to Sweden’s national treatment programme for cirrhosis of the liver, approximately 1,400 Swedes die annually as a result of the disease. According to the same source, every year between 5,500 and 9,000 Swedes are in contact with the healthcare service due to cirrhosis of the liver.

Severe liver disease has a multitude of symptoms. Among them are severe fatigue and severe itching. The itching occurs mainly in those who have problems with the flow of bile, and can be debilitating – acute and unrelenting, it can make it impossible to sleep. Sometimes severe itching is the main indication for transplantation, especially for patients with PSC.

Test can estimate fibrosis risk

When it comes to liver disease as a result of lifestyle habits, liver doctors work towards a clear goal: they want to identify patients who have established fibrosis, on the way to cirrhosis – before cirrhosis has had time to develop. One of the tools for this is the FIB-4 test. It can be used in primary care and gives a rough estimate of how likely it is that advanced fibrosis is present.

“FIB-4 is based on blood tests that cost very little. It may be worthwhile to do this in patients where there is reason to suspect fatty liver disease,” says Hannes Hagström.

This includes people who consume a lot of alcohol. But when it comes to excess weight and obesity, the situation is more nuanced. Even people of normal weight can have a fatty liver with fibrosis development, explains Hannes Hagström. These are usually people with little muscle mass and a large amount of abdominal fat, but whose BMI puts them in the “normal weight” range.

Upon closer examination, this type of fatty liver disease is very often driven by what is known as metabolic syndrome. This includes a large waist circumference and insulin resistance, which are precursors to type 2 diabetes. So are high blood lipids and high blood pressure. A sedentary lifestyle and smoking contribute to the condition.

Metabolic syndrome is bad for the liver

Thus, there are numerous paths to a diseased fatty liver in which more and more healthy tissue is converted into fibrosis. Obesity with a high BMI is one way to end up there. Metabolic syndrome is another, while established type 2 diabetes is a third.

In short, the more complications a patient has that are tied to obesity and a large waist circumference, the greater the risk of liver disease. People with established type-2 diabetes are particularly vulnerable.

In somewhat more detailed terms, metabolic syndrome increases the risk of several diseases, such as kidney disease, cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. Liver disease can also be added to the list – fatty liver with fibrosis development is the liver’s manifestation of metabolic syndrome.

Not enough people are aware of this – neither in healthcare nor in the general public.

Hannes Hagström has a concrete piece of advice:

“If you are obese, have type 2 diabetes, or consume a lot of alcohol, you can ask your primary care physician to do a FIB-4 test. This is in accordance with the guidelines we have for cirrhosis of the liver,” he says.

If the test arouses suspicions of a more severe degree of fibrosis (grade 3 or 4 according to the staging), a special ultrasound examination is recommended. This is called an elastography and is done with FibroScan technology. The patient lies on their back, and via “knocks” on the stomach, it is possible to assess how stiff their liver is. A liver with a lot of fibrosis is as stiff as a Parmesan cheese, while a healthy one quivers like a sponge.

"This is a way to use primary care providers to diagnose fatty liver disease with fibrosis development in asymptomatic patients. That increases the chances of slowing down the progression towards cirrhosis by giving them an opportunity to make necessary lifestyle changes or start taking medication to lose weight,” says Hannes Hagström.

A new model for screening

He has also investigated a new screening model aimed specifically at people with type 2 diabetes. As part of one study, the researchers lent a FibroScan machine to a fundus photography clinic, as people with type 2 diabetes should take fundus photo tests on a regular basis. When the patients were called in for a test, they were offered the opportunity have their liver examined. The offer was repeated when they came to the clinic. Three out of four – nearly a thousand people – accepted. Half of them had fatty liver and five per cent had increased liver stiffness, which indicates the formation of fibrosis.

“People with diabetes have their kidneys and fundus examined regularly to prevent complications, but the current diabetes care guidelines don’t address liver health. This is one of several examples of how healthcare also needs to pay more attention to liver health,” says Hannes Hagström.

But FibroScan machines are expensive, and many primary care providers cannot afford one. The placement at a fundus examination clinic was carried out within the framework of a study. And even when one does manage to diagnose people at this stage – what treatment is available?

There are currently no medications for fatty liver disease. It is up to the patient to make changes to their diet and exercise routines, with the goal of losing weight. They are advised to follow the Mediterranean diet or the Nordic Nutrition Recommendations, which both emphasise healthy fats, more vegetables, whole grains and fish. The dietary changes must be combined with more physical activity.

“These patients need to lose weight for several reasons. They may already have type 2 diabetes or other diseases, so they’ve already gotten dietary advice and information about physical activity. But sometimes patients become extra-motivated when they hear about the risk of cirrhosis,” says Hannes Hagström.

The guidelines for cirrhosis recommend a 10% weight loss in patients with fatty liver disease. This can trim fat from the liver, slow down the progression of fibrosis, and in some cases, the liver can recover. Physical activity is also recommended. Although it does not lead to weight loss, it seems to have an effect on the amount of fat in the liver. The guidelines also mention anti-obesity drugs and bariatric surgery.

“The fact that so many people have unhealthy lifestyles is a major problem that no single doctor or researcher can overcome. If we really want to tackle the problems of excess weight and obesity, we need political action. It has to get easier to exercise and eat according to the recommendations we have, as well as more obvious that we need to do so,” says Hannes Hagström.

Facts: A gland with many functions

The largest organ in the abdomen is a chemical plant with several hundred tasks. Here are some of the most important ones.

Production of vital substances. The liver produces proteins, sugars, fats and hormones. The liver regulates metabolism and also produces substances important for the blood coagulation system.

Production and excretion of bile. This greenish-yellow body fluid dissolves and breaks down fat in food so that it can be more easily absorbed by the intestines.

Storage of energy, vitamins and minerals. In the liver, excess blood sugar is converted into glycogen and stored until this energy is needed to maintain a steady blood sugar level. Vitamins and minerals are also stored in the liver, to be portioned out when needed.

Immune support. The liver eliminates bacteria that enter the blood via the intestine and contributes to the body’s immune system.

Detoxification. Medications, alcohol and other toxic substances are broken down in the liver. The waste products are excreted into the bile or blood and can then leave the body via faeces or urine.

Photo: Jens Magnusson

Photo: Jens MagnussonRead more articles about medical research

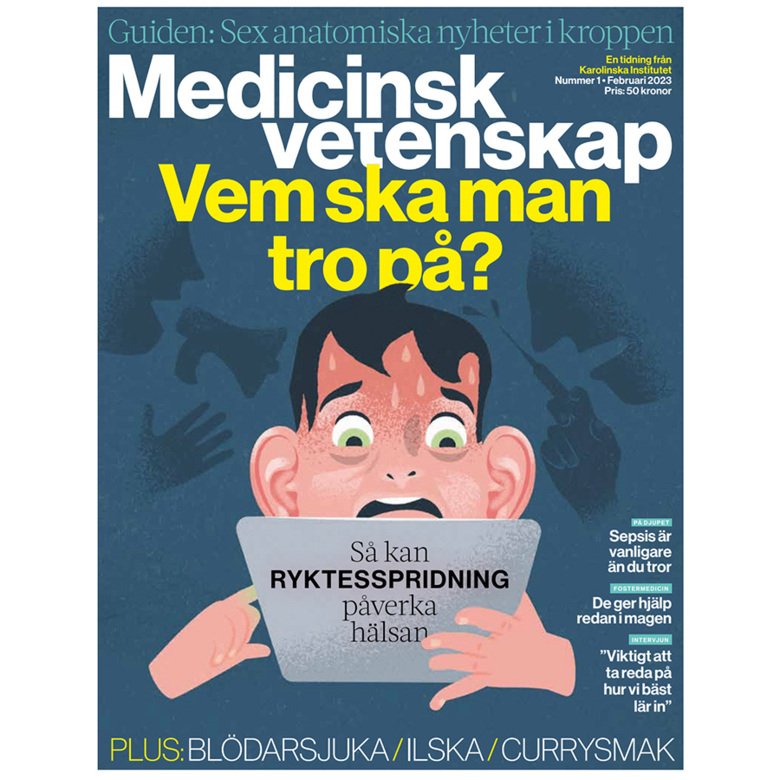

Read about the latest in medical science in Karolinska Institutet's Swedish language popular science magazine Medicinsk Vetenskap. Subscribe now!