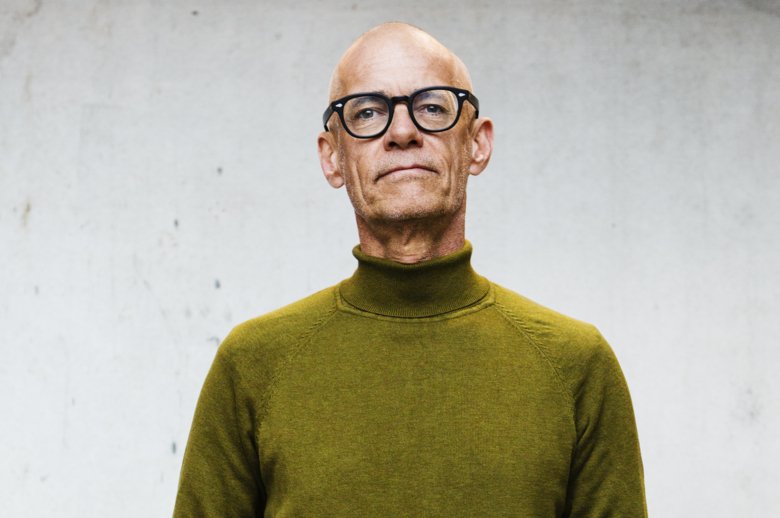

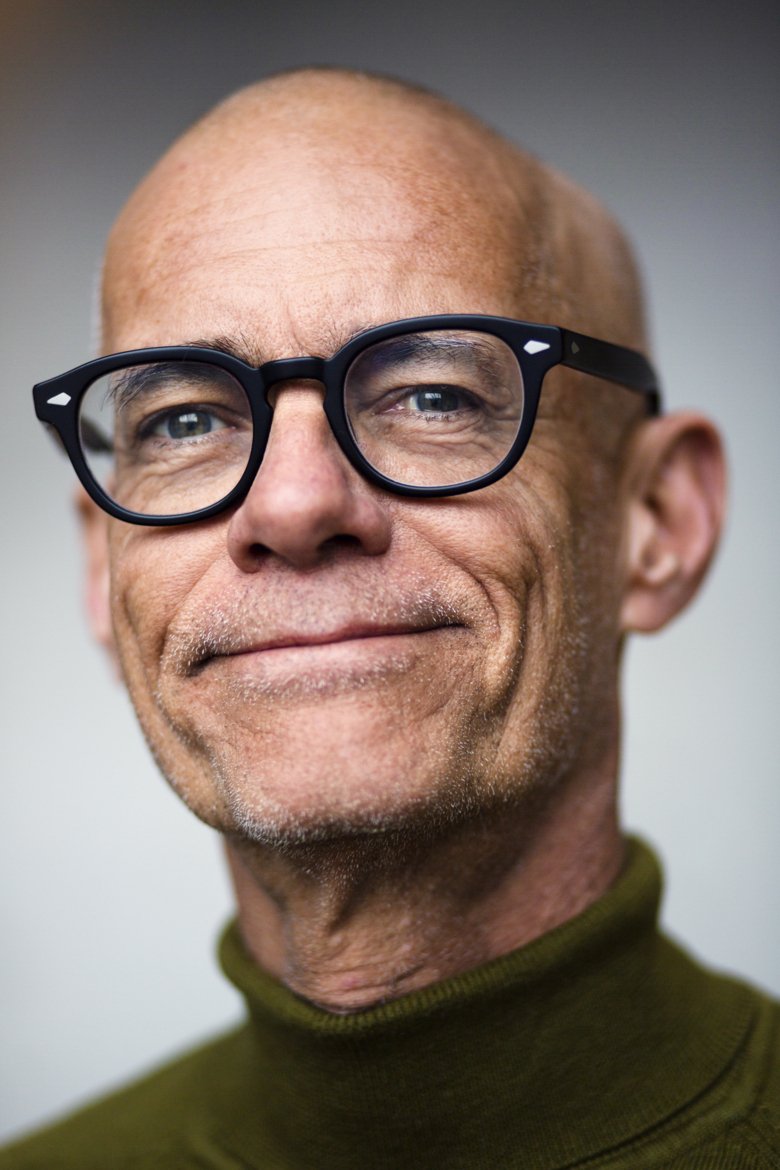

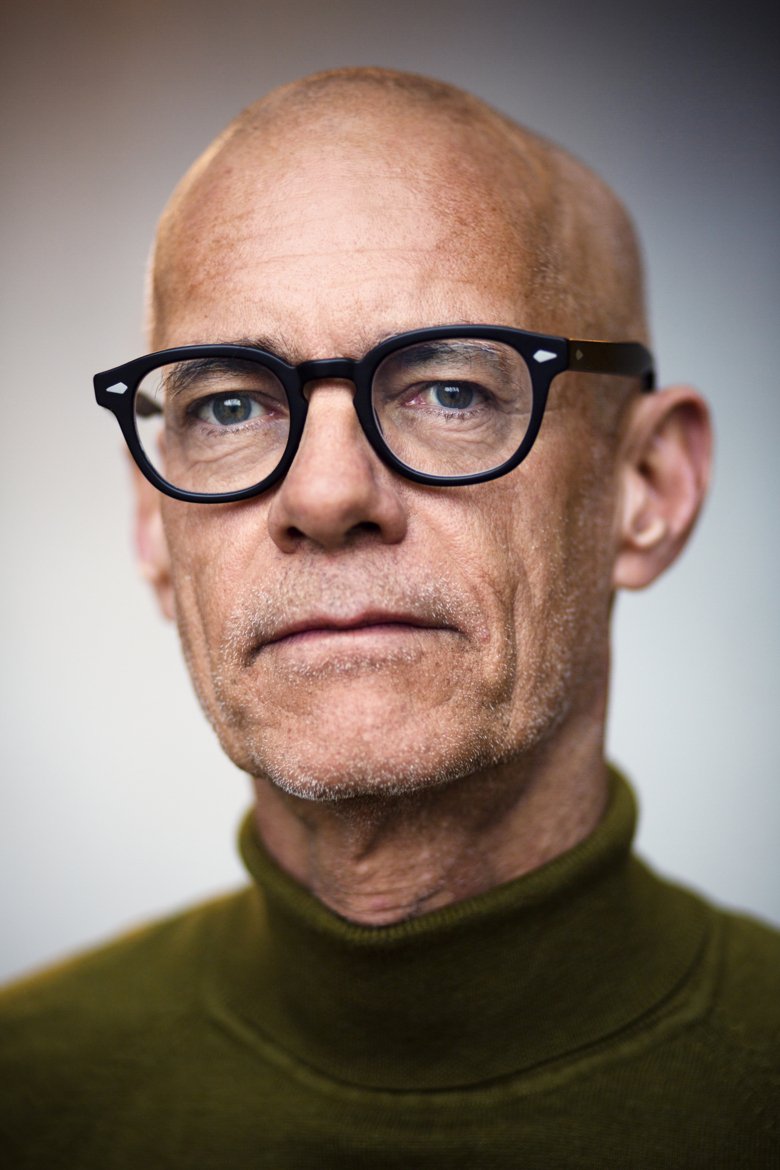

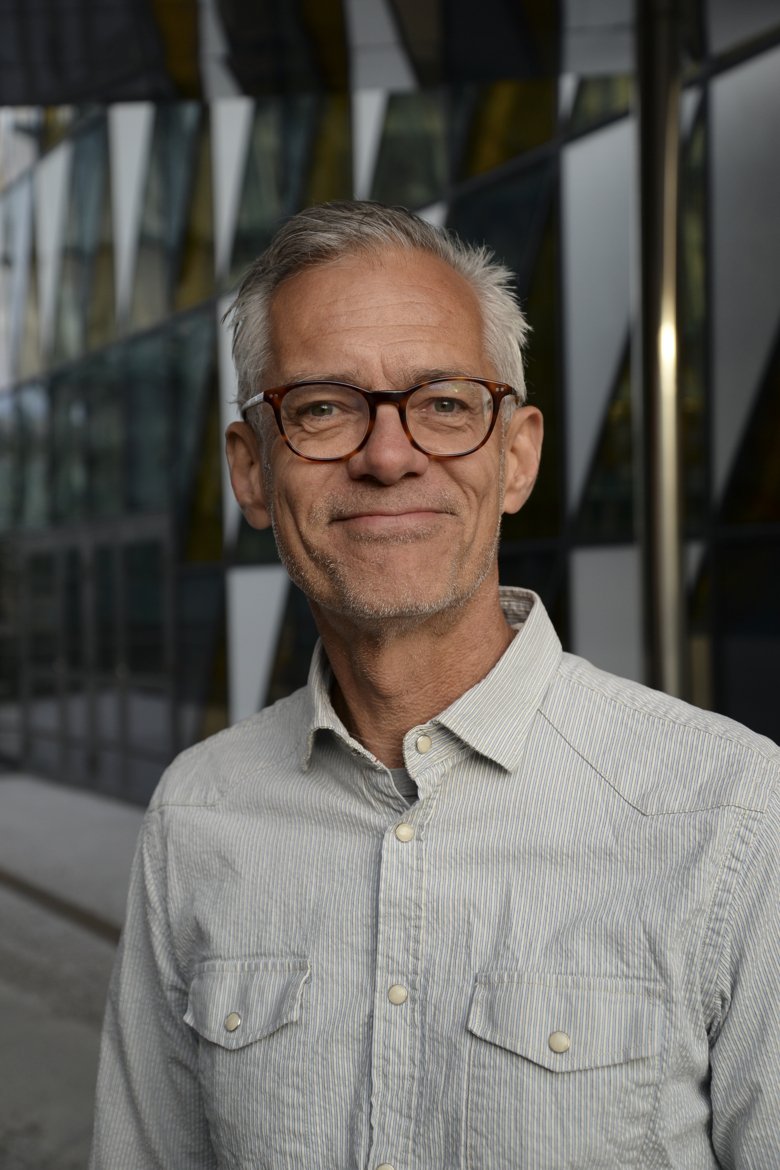

Johan von Schreeb wants to create order in chaos

When others run away from bad things, Johan von Schreeb can be found dashing towards them. He has a wealth of experience in bringing order to chaotic situations – but as an administrator, he’s a complete disaster. Meet the professor who wants to control the health crises of the future.

Text: Cecilia Odlind for the magazine Medicinsk Vetenskap no 2, 2022

The sound of aircraft can be heard in the background as I interview Johan von Schreeb. He’s in Western Ukraine to train staff in disaster medicine and to support the World Health Organization (WHO) on the coordination of relief initiatives. After the global pandemic spanning several years, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and an increased security threat to Sweden, disaster medicine is suddenly a red hot topic. It was a different story when Hans Rosling and Johan von Schreeb founded the Centre for Research on Health Care in Disasters at Karolinska Institutet 20 years ago.

“This subject wasn’t included in medical training. People here in Sweden seemed to think disasters were outmoded and remote. They weren’t something we needed, much like we’ve seen in shelters up until now,” he says.

Perspectives altered during the COVID-19 pandemic, when Sweden’s disaster management was put to the test.

“I was impressed by the fact healthcare professionals were capable of changing. But I was disappointed that there was no acknowledgement at management level that patient safety was under threat: it would have been clearer to state that we were facing a catastrophic situation,” says Johan von Schreeb.

He’s spent much of his professional life combining research and training in disaster medicine with emergency medical response initiatives all over the world, from Afghanistan and Rwanda to the Beirut port bombing and Ebola-stricken Sierra Leone.

He reckons that combining fieldwork with research provides an opportunity to observe needs or problems that can then be evaluated, developed and improved with the help of research.

Becoming a professor never a goal in itself

By way of example, he cites the availability of blood, which can present a problem when people have been injured in wars or disasters. In this regard, Johan von Schreeb and his colleagues have been investigating the chances of taking blood from a bleeding chest and returning it to the patient.

“This is known as autotransfusion, and it’s an underrated method that can be used when blood is in short supply. Knowing how and when it can be used presents a challenge,” he says.

But it can be difficult to do research while also running emergency response initiatives. Data is often unavailable, and the situation is uncertain and difficult to predict.

“We often end up with best practices rather than evidence. How an intervention can be made simple enough to work in chaos. This is something you can only understand by actually being there and observing. So some of my research has to take place in the complex environment resulting from disasters,” says Johan von Schreeb.

He views research more as a means rather than an end in itself. Being a professor and having science as an anchor gives a different weight to what he does and says.

“For me, becoming a professor has never been a personal goal in itself. But academia offers excellent tools for systematically addressing the health challenges that have to be dealt with in a disaster.”

As part of his doctoral thesis, Johan von Schreeb studied international health response initiatives in the event of disasters and found that they were late, poorly adapted to health needs and lacked coordination.

“Disaster response initiatives are a good thing, but that doesn’t automatically mean they do good and are responsive to needs. I’ve noticed it’s important to be critical, especially when intentions are good,” he says.

The work on his thesis eventually led to the Emergency Medical Teams initiative, a kind of global 112 number that disaster-stricken countries can call for assistance from WHO. It relies on the quality of those offering help (such as field hospitals) and their willingness to be coordinated. What triggered this initiative was world’s rather “pathetic” response following the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, according to Johan von Schreeb.

“There was utter chaos. And I’m referring not to the effects of the earthquake, but to the 450-odd medical teams that descended on Haiti. There was a lack of systems, mandates and tools for coordination,” he says.

A guarantee of good care

Today, there are international emergency response teams classified by WHO according to criteria developed by the Emergency Medical Teams initiative, as a kind of guarantee of good care.

Johan von Schreeb’s job on a number of occasions has been to assist the affected country with coordination, most recently in Ukraine. He’s also trained healthcare workers there on how to sort patients in mass casualty situations using a method developed at Karolinska Institutet.

“You can get the priorities to become instinctive by keeping things simple and practising over and over. This is a huge help in a disaster situation, and it reduces the panic that can so easily arise when large numbers of injured people have to be dealt with,” says Johan von Schreeb.

This will provide a specific way of helping healthcare providers to deal with emergencies. But that said, there are several other, less pressing health challenges. Common conditions such as diabetes, heart attacks or childbirth are often overlooked, and vaccination programmes can’t be sustained. Many people lack basic necessities such as food, water and sanitation. In Ukraine, there’s also psychological trauma to deal with when children are torn away from their parents and people experience anxiety and fear.

“These various challenges need to be addressed with knowledge and experience, not just good intentions,” says Johan von Schreeb.

His research team is studying how the vulnerability of countries varies in correlation to different health threats in order to assess the type and severity of health problems in the wake of disasters. Before travelling to a disaster-stricken area, Johan von Schreeb tries to build up a picture of the vulnerability and capacity of the community and the health system in order to assess needs.

“These include vaccination coverage, literacy, how much money is available for healthcare, the distribution between private and public care. All these factors, together with the type of disaster and the number of people affected, determines what initiatives are needed,” he says.

The healthcare budget in Ukraine is five per cent of the Swedish budget, per person. But here, there are still four times more hospital beds per person than in Sweden.

“So there’s no shortage of hospital beds. But that said, specific training is needed on advanced treatment of war injuries. We’ll have to monitor long-term needs,” says Johan von Schreeb.

Besides the vulnerability analysis, there’s also the time aspect to take into account. Personally, he thrives on the acute phase.

“Disasters all have different phases. I work best at the beginning. My thoughts are sharper, I can focus, delegate and weed out anything that’s unimportant. But everything slows down when that initial intense phase is over. That’s the stage when not everything is possible, things take forever and bureaucracy is always on hand to put a spanner in the works and prevent quick decisions being made. That’s the point at which I have nothing more to add,” he says.

To deal with future health crises

As the doer he is, Johan von Schreeb wants to spend his time doing the things that make a difference. Colleagues testify that it can be difficult to get his attention for bureaucratic evaluations, and he himself has described administration as ”strangleholds on creativity”.

“I’m a terrible administrator, but a good improviser. Fortunately, I have excellent colleagues,” he says.

Johan von Schreeb recently took up the post of director of Karolinska Institutet’s newly established Centre for Health Crises, a role for which he has to be regarded as a perfect fit. He reckons that one important job will be to train new researchers with a broad and outward-looking perspective.

“We’re planning a national research school where doctoral students work part-time in ‘real life’ at different agencies such as the National Board of Health and Welfare, the Public Health Agency of Sweden or WHO so as to avoid their research becoming too theoretical and restricted. Sharing experiences provides enrichment in two directions. It’s also important for the younger generation to get out there and work on assignments,” he says.

The main objective of all work at the centre is to build up a good capacity to deal with future health crises both in Sweden and elsewhere. The timing is perfect.

“Suddenly, the perspectives all converge: ’I think Hans Rosling would have been proud that the studies we’ve done from disasters in low-income countries are now relevant and topical to health crises in Sweden too,” he says.

Facts about Johan von Schreeb

Name: Johan von Schreeb.

Title: Surgeon and Professor at the Department of Global Public Health, Karolinska Institutet. Director of the Centre for Health Crises.

Age: 60.

Family: Wife and two adult children.

Motto: “No regrets”.

How he likes to relax: Sailing his catamaran and writing, including Tankar för dagen [Thoughts for the Day] for P1. He also works with the Candyland art gallery, which he founded together with eight artist friends in 2004. “We arranged a forest salon during the pandemic”.

Role model: Professor Hans Rosling. “He wasn’t all that great a supervisor – but he was an incredible inspirational figure. I hear his voice all the time: ‘Johan, you have to think!’”

Best research feature: I’m an opportunist, I grab opportunities wherever they arise.

Johan von Schreeb on...

… hope:

Evil is collective, but goodness is individual. I’ve met many people during disasters, often women, who’ve continued to stir pots and ladle out food with aplomb. Goodness is everywhere, it gives me hope.

… hopelessness:

Ignorance can make me feel hopeless. When people stop caring, without reflecting on what things would be like if they themselves ended up in the same vulnerable situation.

… Swedish security:

All Ukrainian families have experienced war, but this experience is something many Swedes lack. Paradoxically, as a result many Swedes are worried, while there’s also denial that we too might be affected.

… favourite country:

I like Lebanon very much. People there make the best of situations, despite all the hardships they’ve suffered. They always find opportunities to live for the moment and go dancing.

More reading

Photo: Andreas Andersson

Photo: Andreas AnderssonHe is the director of KI's new Centre for Health Crises

Johan von Schreeb, Professor of Global Disaster Medicine and Head of the Centre for Research on Health Care in Disasters at Karolinska Institutet, has been named Dorector of KI’s newly established Centre for Health Crises.

Photo: Getty Images

Photo: Getty ImagesDonation to KI’s Centre for Health Crises

Karolinska Institutet’s Centre for Health Crises is to receive SEK 15 million grant from Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation. The money will be used to build up the centre and develop its activities over the coming two years.

Photo: Getty Images

Photo: Getty ImagesKI team to Moldova to conduct mass casualty exercises

Six people, members of staff or affiliated, from KI went to Moldova on short notice to support the healthcare system there by conducting mass casualty exercises and training in triage and treatment of war wounds. The work was done through KI’s Centre for Health Crises, on a request from the WHO.