Lennart Nilsson in close collaboration with researchers throughout his life

As reported earlier, renowned photographer Lennart Nilsson has passed away. He was born on 24 August 1922 and died on 28 January 2017. Lennart Nilsson began taking pictures at an early age and sold his first picture to the Dagens Nyheter newspaper at the age of 16. When he turned 90, he donated his photographic equipment to Karolinska Institutet, where he had worked since the 1970s.

Lennart Nilsson produced innumerable illustrated features for Swedish weeklies during the1940s and 1950s and later also for international magazines. He first achieved international fame in 1947 with his pictures from polar bear hunting in Svalbard. They were published in Life magazine, one of the most respected illustrated weeklies in the western world, and caused much debate. One of the pictures shows a polar bear cub with a rope around its neck trying to hug its dead mother.

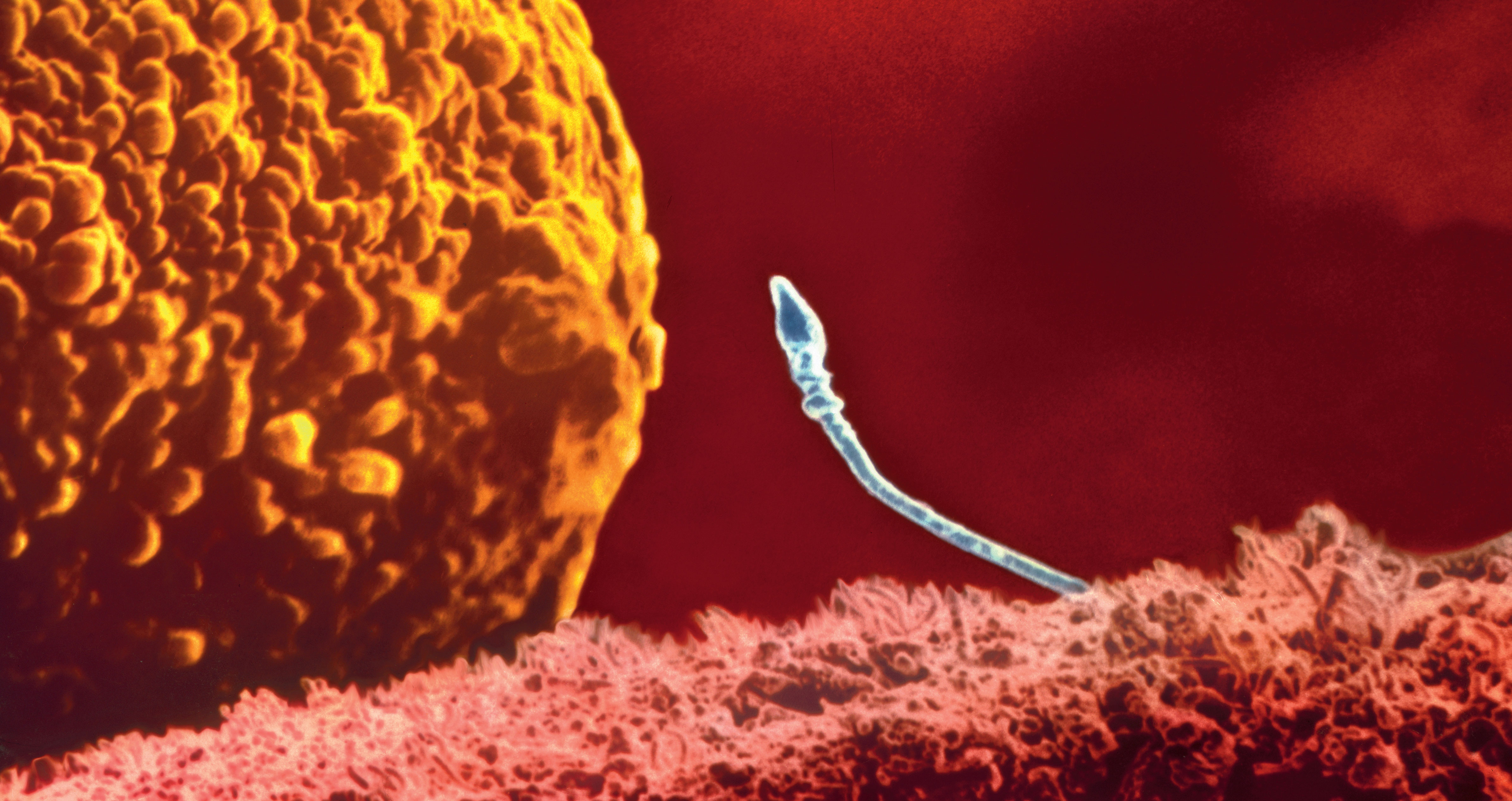

In the mid-1950s he began experimenting with different photographic techniques to be able to make extreme enlargements. His great international breakthrough in medical photography came in 1965 with his images of human foetuses. He had begun the project twelve years earlier, in 1953, and the images resulted in a 16-page feature in Life. The entire edition of eight million magazines sold out in a few days.

His book A child is born was published later the same year. The book has been translated into some 20 languages and republished several times.

For anyone looking at the pictures Lennart Nilsson took up through the 1970s, he seems to be everywhere. He was court photographer to the Swedish royal family, he photographed pygmies in the Congo, and Dag Hammarskjöld when he was appointed Secretary-General of the United Nations. Lennart Nilsson alone was allowed to enter Hammarskjöld’s new office.

Close collaboration with researchers

He worked closely with researchers at Karolinska Institutet from the 1970s until he was more than 90 year old. He visualised medical research and helped millions of people to better understand the human body. His pictures of the inside of the body can also be seen as works of art. He had a unique sense of form, colour and light but he always felt that the narration was the focus – not the picture in itself. “A photographer should record, not direct.” This approach eventually made him a master of waiting for the perfect moment and many of his medical photographs took several years to evolve from idea, through experiments, to finished picture.

Karolinska Institutet appointed him Honorary Doctor of Medicine in 1976 and his work has been of great importance to the university. Throughout his career he continued to push the boundaries for what is possible in medical photography. Among other things he photographed the viruses that cause HIV and avian flu and the parasite that carries malaria -- and always with the perfect picture as his ultimate objective. A sign on the wall of his laboratory at Karolinska Institutet read “Nothing is so good that it cannot be improved”.

If there had been a Nobel prize for photography, Lennart Nilsson surely would have won it. He himself said that he never thought along those lines. He saw himself as a journalist and his driving force lay in “showing what is close to us, what we all know, in new ways” and his foremost objective was to surprise and touch people. As proof of his success he received a great many prestigious prizes and awards, including “Picture of the Year”, “The Hasselblad Prize”, and an Emmy Award. For Lennart Nilsson, the individual viewer’s reaction to his pictures was more important than fame.

A photography prize named after Lennart Nilsson

The Lennart Nilsson Award – the world’s foremost award in scientific and medical photography – was instituted in 1998 and is awarded annually by Karolinska Institutet.

Lennart Nilsson had no formal education in medicine, although he had had plans to study medicine at KI in the late 1950s. He never intended to work as a doctor but he had an inquisitive mind and wanted to learn more, something that was part of his nature. He was advised against medical studies, however, by senior lecturer Axel Ingelman-Sundberg, who thought it would be a waste of his time. He nonetheless became a professor when the government awarded him the title in 2009 for “making the invisible visible and documenting the interior of the human body with scientific precision”.

In 2012 he received the Karolinska Institutet Jubilee Medal (Gold class) for his life-long ground-breaking work on developing and rejuvenating the medical photograph. In conjunction with the award, he donated his photographic equipment to Karolinska Institutet.

Lennart Nilsson was 94.

Text: Jenny Ryltenius