Gonçalo Castelo-Branco wants to understand what lies behind MS

His research shows molecular changes in brain cells when a person develops multiple sclerosis (MS). But it is still unclear whether these changes contribute to - or even protect against - the development of the disease. Gonçalo Castelo-Branco is open to the answer.

Text: Cecilia Odlind, first published in Swedish in the magazine Medicinsk Vetenskap no 1 2025

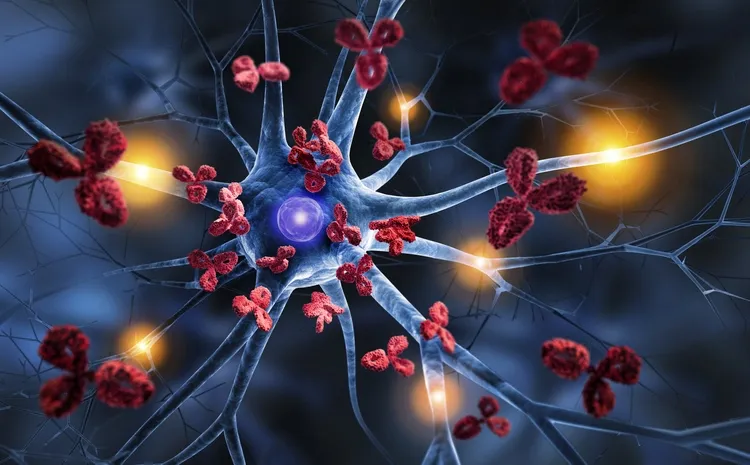

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disease where myelin, the protective layer wrapped around nerves, and which is necessary for electrical impulses transmission, is attacked. This can cause numbness and muscle weakness that occur in relapses in those affected. However, many details of how the disease unfolds are still unclear. Professor Gonçalo Castelo-Branco is trying to advance the understanding and treatment of MS by mapping out exactly what happens step by step. His research group has been particularly interested in a certain type of cell called oligodendrocytes, which are common in the brain and spinal cord. One of their functions is precisely to produce myelin. Oligodendrocytes are formed from progenitor cells, a type of specialised stem cell.

“It has long been hypothesised that MS is caused by something going wrong in the immune system. But our research and that of others shows that oligodendrocytes also play an active role in the disease, they are not just a passive targets", says Gonçalo Castelo-Branco.

Single-cell technologies

For instance, his research group uses single-cell technologies, which allow to measure and track RNA expression in individual cells over time. Thanks to these and other modern methods developed in the last fifteen years, there are now entirely new possibilities to study how cell properties change in disease in detail.

Gonçalo Castelo-Branco and his colleagues made a discovery a few years ago.

”We saw that some of the oligodendrocytes, as well as their progenitor cells, changed and began to exhibit the same characteristics as immune cells. This was surprising", he says.

But exactly what it means that the oligodendrocytes change and more closely resembling immune cells in MS, researchers do not yet know. Is it something that goes wrong, causing them to change properties and thus signal the immune system to attack them? Or is it the opposite, that the change is a response to try to slow down the disease development and avoid the attack? And could it be that these cells have one role early in the disease and another role later?

The goal is to understand this process and then be able to influence the early change of these particular cells.

“We might be able to steer them in a favourable direction. However, our research group's expertise is to map fundamental disease mechanisms. Clinicians or companies can take the lead in developing drugs based on the knowledge we have and are acquiring", says Gonçalo Castelo-Branco.

The research in his group rests on four pillars: computational biology, development of techniques for analysing gene activity in individual cells and tissues, studies on human cells, and neuroscience and immunological studies on mice.

“MS is a physiologically very complex disease. To be able to study the whole picture, mouse models are still needed, that is, mice that mimic cellular changes to those humans have in MS. There are differences, but there are also some similarities that can be used to understand complex processes in MS. But in the future, I hope we will be able to use so-called organoids, a kind of mini-organs created on the dish, although it will take time to recreate the complexity that mirrors the damage that occurs in MS,” says Gonçalo Castelo-Branco.

Biomarkers reveal conditions in the brain

A difficulty with studying diseases that affect the human brain is that you cannot take samples from it. One trick could be to use biomarkers that reveal the condition of the brain. Here, the researchers have an idea based on studies from another field.

“Normally, DNA is found inside the nuclei of our cells. But free DNA also occurs in the blood. Previous studies have shown that by analysing such circulating DNA and chemical modifications in DNA-associated proteins, cancer can be detected", explains Gonçalo Castelo-Branco.

Now, together with his colleagues Fredrik Piehl and Maja Jagodic, both at Karolinska Institutet, he wants to investigate whether circulating DNA can be analysed in a similar way to detect changes in MS.

“When the immune system attacks oligodendrocytes causing them to die, their DNA eventually leaks into the blood. The idea is to measure and analyse the circulating DNA from oligodendrocytes to obtain an early biomarker for MS, that can also be used to measure the effects of a treatment", says Gonçalo Castelo-Branco.

MS is usually described in two phases. During the first 15–20 years, inflammatory activity is high, and nerves are attacked and destroyed. The disease then occurs in relapses, with alternating symptom- and symptom-free periods. This is followed by a so-called progressive phase with increasing loss of motorical functions. In the last 30 years, many new drugs have been developed, mainly targeting the immune relapses. Another important goal of Gonçalo Castelo Branco's research is to find better treatment for the progressive phase.

”We have shown that there are two parallel tracks in the development of the disease. Peripheral immune cells enter the brain and spinal cord and cause damage, leading to relapses with functional loss. But even before that happens, oligodendrocytes and other cells have changed throughout the spinal cord. We believe that this process is more connected to the progressive phase of the disease and that it starts much earlier than previously thought. Here, we have seen that glial cells, which includes oligodendrocytes, play an important role. If we understand this process, we might find better treatments for this phase of the disease", says Gonçalo Castelo-Branco.

Vaccines to be tested

Why some people develop MS is not entirely clear, but researchers have found a number of mutations that increase susceptability for MS. About three years ago, a large epidemiological study published in the scientific journal Nature, showed that infection with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) increases the risk of developing MS.

“However, more than 90 percent of us have antibodies against EBV in adulthood and have thus been infected by the virus, so additional components must be required, such as other environmental factors and mutations in certain genes. Several clinical trials with vaccines against EBV are currently underway. If the hypothesis is correct, fewer of those who received the vaccine should develop MS in the future. That would be an important breakthrough,” says Gonçalo Castelo-Branco.

Some researchers, such as Tomas Olsson at Karolinska Institutet, have proposed a mechanism for how the virus could trigger the disease.

“Ebv has proteins similar to those found in oligodendrocytes and other cells in the brain. The hypothesis is that the immune system initially attacks EBV and then mistakenly starts attacking its own cells. But whether this is the case or not remains to be further investigated,” says Gonçalo Castelo-Branco.

He considers that hypotheses are being constantly re-evaluated in science.

”We researchers are often wrong in our hypotheses. And thus it is very important to listen to each other to gain new perspectives and see other possible solutions,” he says.

The solution is therefore collaboration, according to Gonçalo Castelo-Branco, who considers that this is one of his strongest qualities as a researcher.

”I am good at working together with others, both within and outside my research group. Research IS collaboration. Together we can understand much more", says Gonçalo Castelo-Branco.

About Gonçalo Castelo-Branco

Name: Gonçalo Castelo-Branco.

Title: Professor of Glial Cell Biology at the Department of Medical Biochemistry and Biophysics, Karolinska Institutet.

Age: 48.

Family: Wife and two children, aged 13 and 16. Large family in Portugal and large extended family in Sweden.

How I relax: I am involved in my children's handball activities.

Role model: My brother, who is nine years older than me and became a neuroscientist before me. He inspired me to follow the same path.

Motto: "If it was easy, everyone would do it."

Gonçalo Castelo Branco on...

...celebrations: It is customary to celebrate the publication of a new scientific study with sparkling wine and cake. But I am originally from Portugal so I usually celebrate with my colleagues with Port wine and chocolate instead.

…research music: I always listen to music when I work, to be able to concentrate better. I have a soundtrack for each new publication, and lately I have been listening to the indie pop band The Last Dinner Party.

...research funding: The Swedish Government invests considerably in science, and it is a more long-term funding strategy compared for instance to Portugal, providing better conditions for research.

...the importance of innovation: We have many forward-thinking researchers here, who dared to try to develop completely new technologies for molecular analysis. This has put Karolinska Institutet on the map and has also meant a lot to foster the local research environment.

More reading

Photo: Getty Images,Getty Images/iStockphoto

Photo: Getty Images,Getty Images/iStockphotoSpotlight on MS

Multiple sclerosis is a disease which doctors have partially misunderstood for 200 years. But now there is new information that will change the view of both the course of the disease and the treatment. At the same time, the researchers have found protective factors that are surprising – sun, moist snuff, coffee and alcohol.